Introduction to Nowruz

Nowruz (pronounced no-rooz) is a combination of two Persian words. The first word “now” means new and the second word “ruz” means day; together they mean “New Day.” Nowruz is the name for the celebrations that observe the New Year for many Persian and Central Asian communities. The exact beginning of the New Year occurs when the season changes from winter to spring on the vernal equinox, which usually happens on 20 or 21 March each year. The spelling of Nowruz in English can take many forms, including Noroz, Norouz, Nowruz, and Norooz. For this resource, we have used the spelling Nowruz. The festivities of Nowruz reflect the renewal of the Earth that occurs with the coming of spring. Activities that celebrate the arrival of Nowruz share many similarities with other spring festivals such as Easter, celebrated by Christians, and the Egyptian holiday called Sham Al-Naseem, which dates back to the time of the Pharaohs.

Historical Beginnings

Nowruz is a festival that has been celebrated for thousands of years. It is a secular holiday that is enjoyed by people of several different faiths and as such can take on additional interpretations through the lens of religion. Nowruz is partly rooted in the religious tradition of Zoroastrianism (bolded words are defined on pg. 7). Among other ideas, Zoroastrianism emphasizes broad concepts such as the corresponding work of good and evil in the world and the connection of humans to nature. Zoroastrian practices were dominant for much of the history of ancient Persia (centered in what is now Iran). Today there are a few Zoroastrian communities throughout the world, and the largest is in southern Iran and India.

Persian Cultural Roots

People all over the world celebrate Nowruz, but it originated in the geographical area called Persia in the Middle East and Central Asia. The distinct culture based on the language, food, music and leisure activities that developed among the many people and ethnic groups who lived in this area is known as Persian. Nowruz became a popular celebration among the communities that grew from these Persian influenced cultural areas. While the physical region called Persia no longer exists, the traditions of Nowruz are strong among people in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, India, Pakistan, Turkey, Canada, and the United States. Nowruz is a holiday that is celebrated by people from diverse ethnic communities and religious backgrounds. For the Parsi community, however, Nowruz is very special and is known as their spiritual New Year.

‘That’s something inbred, it’s a part of me. I will always walk around like a Persian popinjay.’

Freddie Mercury | Queen | Farokh Bulsara

Is it Persia, or Iran?

Often the words “Persia” and “Iran” are used interchangeably, but they mean different things. The word Persia comes from the Greek word Pars, which was used to describe the lands that stretched from the Indus Valley in present-day India and Pakistan to the Nile River in today’s Egypt. The Ancient Greeks called the people who lived in these areas ”Persians”. The word ”Iran” comes from Aryan, which was an ethnic label given to ancient peoples who migrated from the Indus Valley area towards Central Asia. In 1935, the state of Persia officially changed its name to Iran. Therefore, Iran is used to describing the contemporary country and its people, while Persia refers to the broader culture, many ethnic groups and an ancient history that some say goes back 3000 years. Persian is also the name for the language spoken by Iranians.

Rituals and Traditions

Nowruz is a time for family and friends to gather and celebrate the end of one year and the beginning of the next. Children have a fourteen-day vacation from school, and most adults do not work during the Nowruz festivities. Throughout the holiday period friends and family gather at each other’s houses for meals and conversation. Preparing for Nowruz starts a few weeks prior to the New Year with a traditional spring cleaning of the home. At this time it is also customary to purchase new clothing for the family and new furniture for the home.

Chahar Shanbe Suri: The Fire Jumping Traditions

On the night of the last Wednesday of the old year Chahar Shanbe Suri, in Persian, is celebrated. During the night of Chahar Shanbe Suri people traditionally gather and light small bonfires in the streets and jump over the flames shouting: “Zardie man az to, sorkhie to az man” in Persian, which means, “May my sickly pallor be yours and your red glow be mine.” With this phrase, the flames symbolically take away all of the unpleasant things that happened in the past year. Because jumping over a fire is dangerous, many people today simply light the bonfire and shout the special phrase without getting too close to the flames.

Tahvil: The Exact Moment of the New Year

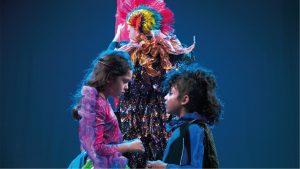

Families return home after the events of Chahar Shanbe Suri and wait together for the exact moment when the vernal equinox occurs, in Persian called Tahvil. Today people know the moment of Tahvil through searching on the Internet or looking in the newspaper. However, before these sources of information were available, families knew that the New Year was close when a special person called Haji Firooz came to the neighborhood to sing, dance and spread the news of Nowruz. Haji Firooz is usually dressed in a red satin outfit with his/her face painted as a disguise. When the New Year is just minutes away families and friends gather together and wait for Tahvil to occur. Right after the moment of Nowruz, the family exchanges well wishes such as “Happy New Year” or “Sal-e No Mobarak!” in Persian. Next, the eldest in the family distributes special sweets and candies to everyone, and young children are given coins as presents. It is also traditional for families and neighbors to visit each other and exchange special gifts.

Haft-Seen Table: The Table of Seven S’s

The most important activity in the celebration of Nowruz is making the haft-seen table. Haft is the Persian word for the number seven and seen is the Persian word for the letter S. Literally, the haft-seen table means a “table of seven things that start with the letter S’. Creating the haft-seen table is a family activity that begins by spreading a special family cloth on the table. Next, the table is set with the seven S items.

Here are some of the items and what they symbolize:

Sumac (crushed spice of berries): For the sunrise and the spice of life

Senjed (sweet dry fruit of the lotus tree): For love and affection

Serkeh (vinegar): For patients and age

Seeb (apples): For health and beauty

Sir (garlic): For good health

Samanu (wheat pudding): For fertility and the sweetness of life

Sabzeh (sprouted wheat grass): For rebirth and renewal of nature

In addition to these S items, there are other symbolic items that go on the haft-seen table, depending on the tradition of each family. It is customary to place a mirror on the table to symbolize reflection on the past year, an orange in a bowl of water to symbolize the Earth, a bowl of real goldfish to symbolize new life, colored eggs to represent fertility, coins for prosperity in the New Year, special flowers called hyacinths to symbolize spring and candles to radiate light and happiness. Each family places other items on the table that are special, for example, the Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, or the Shahnameh, an epic Persian story of colorful kings and princes written around the year 1000 CE.

Another important item to place on the haft-seen table is a book of poetry by the famous poet Shams ud-Din Hafez. Hafez lived in Persian lands during the 14th Century CE and wrote many volumes of poetry and prose narratives. Many Persians consider Hafez to be their national poet, and his historical status is similar to the importance of Shakespeare in the English-speaking world.

Special Foods of Nowruz

Just like other cultural celebrations, many special foods are prepared during Nowruz, depending on the country of origin. One of these dishes, ash-e resteh or noodle soup, is typically served on the first day of Nowruz. This soup is special because the knots of noodles symbolize the many possibilities in one’s life, and it is thought that untangling the noodles will bring good fortune. Another Nowruz dish is called sabzi pollo mahi (fish served with special rice mixed with green herbs). The rice is made with many green herbs and spices, which represent the greenness of nature at spring. Special sweets are also served during Nowruz. Traditional items include naan berenji (cookies made from rice flour); baqlava (flaky pastry sweetened with rosewater); samanu (sprouted wheat pudding); and noghl (sugar-coated almonds).

The Final Day of Nowruz: Sizdeh Bedar

The haft-seen table remains in the family home for thirteen days after the beginning of Nowruz. The thirteenth day is called Sizdeh Bedar, which literally means in Persian “getting rid of the thirteenth.” The celebrations that take place on Sizdeh Bedar are just as festive as those on the first day of Nowruz. On this day, families pack a special picnic and go to the park to enjoy food, singing and dancing with other families. It is customary to bring new sprouts, or sabzeh, grown especially for this occasion. At the park, the green blades of the sabzeh are thrown on the ground or in a nearby river or lake to symbolize the return of the plant to nature. Sizdeh Bedar marks the end of the Nowruz celebrations, and the next day children return to school and adults return to their jobs.

Definitions

Germination: The process whereby seeds or spores sprout and begin to grow.

Parsi: A member of a contemporary Zoroastrian religious group. Parsis live mainly in southern Iran, India and Pakistan, and there are communities in Canada and the United States.

Shahnameh: Written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi around the year 1000 CE. Literally the “Book of Kings”, it is a long narrative that tells the story of the history of Persia from its earliest beginnings to the seventh century CE.

Shams ud-Din Hafez: Popular and widely revered poet who lived from 1320 to 1390 CE. His book of poetry, called the Divan of Hafez, is an important part of many Nowruz activities.

Qur’an: The sacred book of Islam, believed to be a compilation of the words of God as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

Vernal Equinox: The time when the sun crosses the plane of the earth’s equator, making night and day of approximately equal length all over the earth and occurring about 21 March (vernal equinox or spring equinox) and 22 September (autumnal equinox) each year.

Zoroastrianism: The religious system founded by Zoroaster, believed to be a prophet living in Persian lands in the sixth century BCE. It is recorded in the Avesta, or ancient scriptures, which teach the worship of a deity called Ahura Mazda. One of the main principles of religion is the universal struggle between the forces of light and darkness, or good and evil.

International Nowruz Day was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly, in its resolution A/RES/64/253 of 2010, at the initiative of several countries that share this holiday (Afghanistan, Albania, Azerbaijan, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, India, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey and Turkmenistan.

Inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity as a cultural tradition observed by numerous peoples, Nowruz is an ancestral festivity marking the first day of spring and the renewal of nature. It promotes values of peace and solidarity between generations and within families as well as reconciliation and neighborliness, thus contributing to cultural diversity and friendship among peoples and different communities.